Who were the best and worst presidents in American history? It's the sort of barstool conversation bandied about amateur historian and policy nerds like myself on a semi-regular basis. But as this question has come up in recent weeks around the blogosphere it got me thinking about a slightly more discrete question: Who are the best and worst foreign policy presidents of the last 100 years?

After reaching out to host of historians, foreign policy experts, academics and various think tankers here's one stab at answering a question which, in many respects, has no right answer. How you choose the best and worst foreign policy President depends in large measure on what values inform your vision of what a good foreign policy looks like. If you're a foreign policy idealist, Wilson would seem pretty good; a foreign policy realist; you might cast a vote for George H.W Bush or even Richard Nixon. If you prefer your presidents to talk tough, Harry Truman might be your man; if you prefer a more modest and less partisan figure, Dwight Eisenhower might float your boat.

As my list suggests, I tend to lean toward the more restrained, pragmatic realists who are suspicious about the use of force. Conversely, I'm more wary of not only the idealistic and ideologically driven presidents, but also those who use foreign policy, most destructively, as a tool of domestic politics. For the purposes of brevity, I've gone back 100 years from today, and restricted the selections to eleven presidents who fall in the best to worst spectrum (that means no TR, no Clinton and no Taft, Ford, Coolidge, Hoover and Harding). These are the five best, the five worst and the one who is in a category all his own. But half the fun of assembling a list like this is in the writing; the other is in listening to people tell me all the reasons I'm wrong. So have at it.

The Five Best Presidents

#5 The Incomplete: John F. Kennedy

Was John F. Kennedy the worst president of the 20th century as defense blogger Tom Ricks suggests? Not even close. His foreign policy record is a tale of crucial mistakes, significant accomplishments and perhaps above all an evolution in thinking (an unusual trait among presidential office holders). He came into office having dangerously ratcheted up the Cold War rhetoric with his blatantly false warnings of a missile gap with the Soviet Union. His inaugural address, though deservedly praised, pointed the way toward greater US militarism and intervention in the periphery of the Cold War.

His presidency got off to a terrible start with the Bay of Pigs, an epically bad example of presidential mismanagement. But not long after he resisted calls for military action in Laos: an example of bold and assertive leadership from a young president. The Vienna Summit with Khrushchev was amateur hour and contributed to the Cuban Missile Crisis. But JFK's handling of the one incident that brought the world as close to nuclear Armageddon as its ever come is an accomplishment that outweighs any negatives on Kennedy's record. Crisis management is a fairly essential part of the job of president and few of the holders of the top job did it as well as Kennedy did in the Fall of 1962.

The big unknown with Kennedy is, of course, Vietnam. Clearly he ramped up US engagement in the conflict, although clearly never took the step of sending ground troops to fight there - as his successor so flagrantly did.* Would he have escalated? We'll never know. Although the evidence that he would have been perhaps more rigorous in his analysis and decision-making than Johnson is compelling. Also the American University speech given only six months before his death suggests that Kennedy had softened, in part, his hard-line Cold War thinking. It's impossible to fully judge Kennedy's presidency and the detractors and supporters have strong cases to make, but it's easy to imagine that had he lived and continued the foreign policy transformation that was emerging near the end of his life, he could have been one of the great ones.

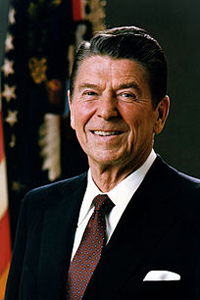

#4 A Tale of Two Terms: Ronald Reagan

When Ronald Reagan came into office in 1980 he had a reputation as perhaps the most stridently anti-Communist presidential candidate in the Cold War era. As President he failed to disappoint. He turned up the anti-Communist rhetoric; branded the Soviet Union an 'evil empire'; raised defense spending significantly; and increased support for anti-Communist rebels, and authoritarian regimes in Latin America, the Far East, Africa and perhaps most enduringly, Afghanistan. By escalating the containment doctrine to one of "rollback" his first term as President saw the Cold War reach, perhaps, its most fever pitch with both sides seriously entertaining the potentiality of nuclear conflict. An ABC television movie, The Day After, which portrayed a post-apocalyptic United States seemed like more than mere fantasy, but a distinct possibility.

Yet, in retrospect, for all his political bluster Reagan turned out to be quite the political pragmatist. When Mikhail Gorbachev took office in 1985, Reagan shelved the tough talk and got down to business, almost making a deal with the Soviet leader to eliminate all strategic nuclear weapons at the Reykjavik summit. But the very fact that he was willing to work with the Soviet premier; that he ignored the heated claims of many of his advisers that the US should remain on heightened sense of alert with the Soviets gave Gorbachev the political space he needed to enact reforms that eventually toppled his country. It's a telling reminder that sometimes restraint is the most effective foreign policy option.

Moreover, for all of Reagan's hawkish image he only ordered one major military intervention during his presidency, Grenada, and he wasn't afraid to cut his losses when necessary as he did in Lebanon after 241 Marines were killed on a peacekeeping mission. While the Iran-Contra affair would become a black mark on his second term in office and it's hard to look past the human toll of his support for anti-Communist and un-democratic groups around the world, he deserves enormous acclaim for helping peacefully end the Cold War (though not 'win' as Reagan partisans are prone to argue).

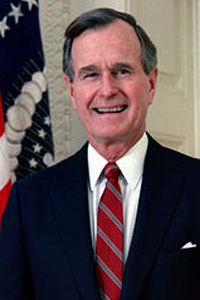

#3 The Underrated: George H. W Bush

Generally speaking when "president" and "Bush" are used in the same sentence these days, rarely does the word "success" also appear (more on that later). But when it comes to the foreign policy performance of the elder President Bush the track record is actually pretty good. He handled the Iraq War with great deftness; of particular note was the assembling of a multi-national coalition and getting a UN Security Council imprimatur to turn Saddam out of Kuwait. By laying out modest, achievable goals for the war and resisting the urge to "go to Baghdad" Bush offered a model for foreign intervention that faithfully subscribed to the Weinberger/Powell Doctrine . . . and was of course flagrantly violated by his son. Nonetheless, the Gulf War bolstered the notion of collective security in the international system and offered a warning to other countries intent on conducting cross-border invasions in the post-Cold War world.

Speaking of the Cold War, while Bush might have been a bit late in supporting Russian reformers, he was able to, in part, manage an international process that brought Soviet troops out of Eastern Europe, reunified Germany and eventually saw the demise of America's greatest strategic threat. All this was achieved with no violence and unfolded in such a way that saw vibrant democracies take root across Europe (if not Russia). That's no small accomplishment (even if the lion's share of credit belongs to European and Russian leaders). In the Middle East, the political pressure he put on Israel after the Gulf War (which hurt his re-election chances) led to the Madrid Peace conference. Even more important, open conflict with the Israeli government contributed, in part, to the election of Yitzhak Rabin and defeat of Yitzhak Shamir in 1991; these were two moves that helped pave the way for Oslo.

On the negative side, Bush's hands-off policy toward the Balkans while true to his realist impulses likely undermined the possibility of resolving the conflict before a full-scale civil war emerged. His encouragement of uprisings in Iraq that he failed to back up with use of force (not to mention a terrible cease fire deal with Saddam that allowed him to suppress Shiite and Kurdish revolts) are black marks on the Bush record. Criticism is perhaps also due for his failure to try and stabilize Afghanistan after the Soviet departure, but it's highly questionable as how to much the United States could have done to alter the situation. His post-Tiananmen support for Chinese leaders was morally dubious but may have, in the long-run, strengthened the process of reform in China. All in all Bush's success in his one-term suggests that had he served another his final ranking might have been even higher.

#2 Dwight Eisenhower: The Runner-Up

Everybody likes Ike it seems (well except of course the Guatemalans, the Iranians, and the Indonesians, and for good reason). His presidency gets high marks from historians and foreign policy analysts alike - and deservedly so.He played nuclear poker beautifully to end the Korean War and also convinced the Chinese from keeping their hands off Taiwan. His policy of ratcheting up the nuclear arms race lessened the chances of US-Soviet conflict and also prevented the military budget from spiraling out of control. His remainder method for defense spending (after domestic priorities the remainder would go to the Pentagon) brought some sanity to what he later dubbed the military-industrial complex.

Ike also gets points for his handling of the Suez crisis and staring down those in his own administration who wanted to support the French militarily when they were getting their clocks cleaned in Indochina. And he used Cold War fears to push for national highway system and more money for higher education, two smart national security investments. From the a political standpoint he quietly helped usher in the downfall of Joseph McCarthy; and more prominently his 1952 campaign had the intended effect of burying the isolationist wing of the GOP and enshrining an internationalist vision in US foreign policy. He was also a non-partisan on foreign policy issues; a far cry from Truman or the presidents who would follow in his footsteps.

As Sean Kay, a professor at Ohio Wesleyan University (and Eisenhower devotee) said to me; "what really made him a great President on foreign policy was his capacity to see American power in more than military terms, and to see the essential relationship between domestic programs, like education, and national security. I could not think of a more appropriate worldview today." It's hard to disagree.

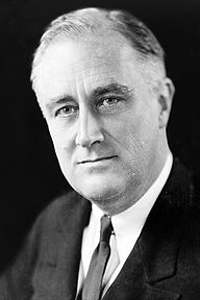

#1 The Gold Standard: Franklin Roosevelt

On the strength alone of winning World War II and handling the delicate diplomacy of dealing with wartime US Allies, like Churchill, Stalin, de Gaulle and Chiang Kai-Shek Roosevelt is far away the greatest foreign policy president of the 20th century. With this record of accomplishment it's hardly even a contest.

When one considers also that he laid the groundwork for the international system, via the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions, he practically floats into the stratosphere. This latter accomplishment is among FDR's most enduring in that it re-shaped the global system after World War II. But even Roosevelt's lesser well-known achievements stand out. The Good Neighbor policy ended (at least temporarily) US military interventions into Latin America and solidified the support of Western Hemispheric leaders for America's larger foreign policy goals.

Critics will rightfully complain that Roosevelt stumbled into conflict with Japan (or manufactured the war in order to ensure a US entry intro to the larger European conflict); or that he sold out the Eastern Europe countries at Yalta. All fair charges, but then they are also reflective of the hard-nosed pragmatism that bookended Roosevelt's idealism. Obviously no president is perfect and even the best ones have their downsides. Indeed, few American presidents fall easily into the great or even really good category - in the 20th century Roosevelt is clearly the one who does.

The Five Worst Presidents

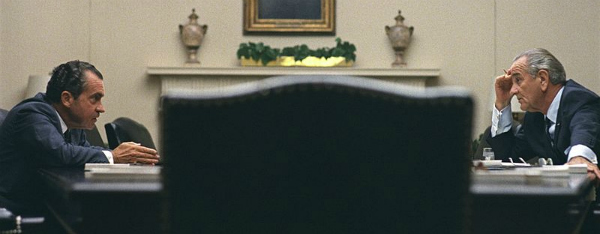

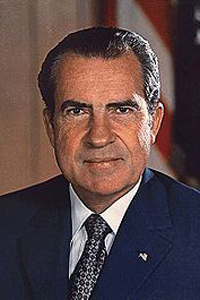

#5 When He Was Good, He Was Good; When He Was Bad, Whoa: Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon is generally considered one of the worst American Presidents - impeachment and resignation tends to have that effect. But his foreign policy record is more mixed. His accomplishments are among the most consequential of the Cold War, in particular, his opening to China in 1971 and his efforts at détente with the Soviet Union. Considering that these had been his two overriding priorities upon taking office it's even more impressive.

Of course the ledger on the other side is pretty ugly. It took Nixon four years to wind down the Vietnam War (with tens of thousands more American dead as a result). This came after he and his top foreign policy adviser, Henry Kissinger, had scuttled a potential breakthrough only days before the 1968 presidential election (an act that to the less charitable might be considered borderline treason). His decision to bomb and then later invade Cambodia led to the ascendance of the Khmer Rouge and the death of a million Cambodians. He escalated the bombing of North Vietnam to get a final peace deal, which led to horrible civilian casualties; and then when that deal was reached his political problems at home over Watergate helped to undermine the case for continuing to support South Vietnam. There was also the deposing of Prime Minister Allende in Chile, Nixon's virtual nervous breakdown during the Yom Kippur War (although Kissinger's subsequent shuttle diplomacy paved the way for the Camp David Accords) and, the stain of Watergate badly undermined the US image in the world.

From the narrow perspective of US interests, Nixon had important successes and might even be considered an above average presidency; but with the fuller range of human consequences of his policies is considered it's much harder to give him a passing grade.

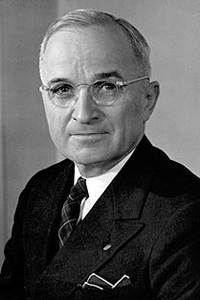

#4 The Overrated: Harry S. Truman

Harry Truman has in the nearly 50 years since he left the White House grown significantly in the estimation of both the public and many historians. To be sure, he deserves enormous credit for protecting and stabilizing Western Europe with the Marshall Plan and the creation of NATO. These are signal achievements but as historians from Robert Dallek and Walter Lafeber to Fredrik Logevall have suggested there is a pretty significant downside to Truman's presidency as well.

First there was Korea. An impulsive response to a cross-border attack that re-shaped American foreign policy. It was the final nail in the coffin of the more modest containment strategy proposed by George Kennan and by default enshrined the notion that the US had a responsibility to contain Communism wherever it showed its fangs. But while the decision to go to war can be considered a debatable one; the failure in rein in Douglas MacArthur's push to the Yalu River, which triggered a Chinese intervention is a disaster that can't be washed away (even by Truman's later decision to fire the general). Considering that more than 20 million North Koreans continue to live in terrible hardship today because of that decision only compounds the mistake.

Beyond Korea, the Truman Doctrine and its declaration that it was the "policy of the United States to support free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures" laid the groundwork for the limitless definition of US national interests that unfolded over the next 60 years. As Kennan would later note, it was one thing to contain Communism in Europe (a goal on which Truman succeeded). It was quite another to broaden that goal to the rest of the world. There is, as a result, a straight line between Truman's foreign policy choices and the war in Vietnam.

Then there was Truman's use of anti-Communist rhetoric for political advantage that turned what might have been a balance of power, geo-political clash into an ideological one. This, of course, also helped to politicize the Cold War in the United States and heightened the issue of anti-Communism. Indeed, few Presidents more flagrantly used foreign policy as a political punching bag as frequently as Truman.

Finally, ask yourself a counter-factual: how would the Cold War have unfolded if FDR had lived out his fourth term, rather than having the inexperienced Truman become the leader of the Free World? It's not hard to imagine that the tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, so deftly handled by FDR during WWII, would have been minimized and a less militarist and dangerous conflict might have emerged. At the very least, as Robert Dallek points out even if superpower, ideological conflict between the US and Soviet Union was inevitable, Truman never really sought to find an alternative.

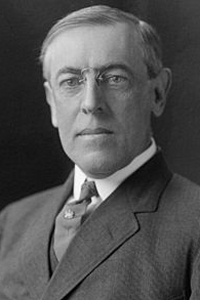

#3 Judge Me Not For What I Did; But What I Said: Woodrow Wilson

One can just easily find foreign policy commentators who will pronounce Wilson the best foreign policy president of the 20th century and those who will call him the worst. The latter argument is tangibly the more persuasive. Wilson was a dangerous interventionist in Latin America and a dangerous utopian in Europe. He sent troops into Haiti, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic and Mexico; all efforts that Wilson convinced himself were intended to further democracy and not US interests. "I am going to teach the South American Republics to elect good men," he once said.

Wilson's willful blindness to the consequences of his foreign policy actions - and his apparent conviction that America's intentions were almost always pure - would define US involvement in World War I as well. Though it helped to end the war in Europe, Wilson was complicit in the disastrous Versailles peace deal. But his greatest failing was in losing the peace at home and failing to build public support for US entry into the League of Nations. The failure of the Senate to ratify the Treaty (aided and abetted by Wilson's stubborn and foolish refusal to negotiate over its terms) contributed to the anti-internationalist backlash that emerged after he left office.

Yet, Wilson's advocacy of self-determination and democracy has carried on. As Fareed Zakaria noted several years ago, "when someone argues in favor of human rights and democracy, advocates self-determination for minority populations or the dismantling of colonial empires, criticizes secret and duplicitous diplomacy, or supports international law and organizations, he is rightly called Wilsonian." The Wilsonian impulse in American foreign policy has both spoken to the "better angels" of the American spirit at the same time that it has led to overly ambitious policies far outside the capabilities and interests of the United States (case in point: George W Bush) - and has matched it with a dangerous and often misguided American exceptionalism. In some respects, one could argue that the rightness of Wilson's vision was matched only by the wrongness of the policies that has generally flowed from it. There is no question that Wilson's idea of America's role in the world has endured; it's far less clear that this has had a positive impact on US foreign policy.

#2 Speaking of Hopeful Idealists: Jimmy Carter

If any president speaks to the failures of Wilsonian foreign policy it would be Jimmy Carter. He came into an office with a focus on human rights but found that the intricacies of global politics don't necessarily allow for US presidents to so easily devalue American interests in the name of promoting national values. With the Somoza regime in Nicaragua, more disastrously with the Shah in Iran and in relations with the USSR, Carter tied himself in knots trying to uphold US interests all the while adhering to a human rights first agenda.** Like Wilson, Carter deserves credit for highlighting the importance of the issue after the excesses of Vietnam, but loses points for producing a foreign policy that was hopelessly muddled.

On the flip side, the Camp David Accords were a significant diplomatic achievement and one that strengthened the US position in the region vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. But the Carter Doctrine to protect the Persian Gulf was an under appreciated mistake that expanded the US security umbrella in the defense of . . . cheap oil. Finally, in the last year of his presidency Carter moved further to the right, expanded the defense budget, heated up the anti-Soviet rhetoric, partly in response to the invasion of Afghanistan but also with one eye on Election 1980 (Like so many of his predecessors Carter allowed politics to play a far too significant role in his foreign policy decision-making). As a result he helped to validate the more strident anti-Communism of his opponent, Ronald Reagan. Good intentions that turned out badly . . . one might even detect a pattern here.

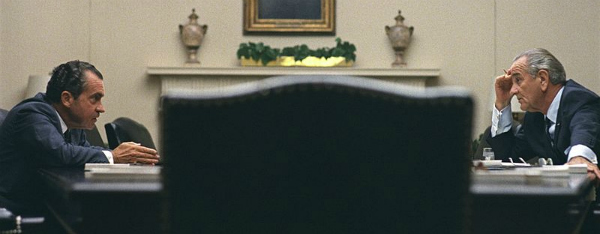

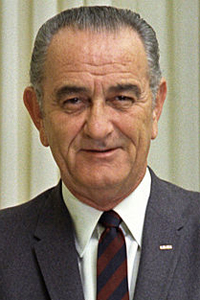

#1 The Worst: Lyndon Baines Johnson

One of the reasons that John F. Kennedy looks pretty good as a foreign policy president is because of how bad the foreign policy performance was of the man who replaced him. Say what you will about Lyndon Johnson's domestic accomplishments. They are impressive. As steward of America's global role, Johnson was a train wreck.

The obvious answer as to why LBJ was so bad is, of course, Vietnam. But it was how he screwed up the war that really explains his terribleness. First, his foreign policy thinking was defined by a knee-jerk misuse of historical analogy (Munich, appeasement etc). Second, a focus on the domestic implications of foreign policy decision-making led him to adopt maximalist positions - and made him deeply fearful of any policy shift that would lead to charges of "retreat." (Johnson was deeply affected by the "Who Lost China" attacks of the 1950s and was apprehensive that he would be attacked in a similar manner if he lost Vietnam.) Third, he derided principled war opposition as unpatriotic (in 1966 he called anti-war advocates "Nervous Nellies") and escalated the conflict surreptitiously, without fully informing the American people. The credibility gap he created on the war went a long way toward undermining the confidence of the American people in their elected leaders.

Lastly, as the country became more enmeshed in the war he was practically immune to information and opinion that contradicted his biases. He surrounded himself with supplicants like Walt Rostow who told him what he wanted to hear and got rid of those who offered a dissenting view (for example, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara).

By the fall of 1967, Johnson had one last opportunity to save his presidency and end the war. Instead he continued to mislead American people about how Vietnam was going and the nature of the enemy threat - an effort capped off by General William Westmoreland's famous 'light at the end of the tunnel' speech. The result was that he hopelessly divided the Democratic Party (a rift that has never completely healed), destroyed his domestic agenda, cost himself a chance at re-election and helped to ensure Nixon's victory in November 1968. Put it all together and you have a President whose foreign policy was one for the ages - and not in a good way.

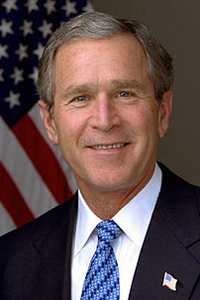

A Category All His Own: George W. Bush

The only saving grace that keeps Lyndon Johnson out of the cellar is that this list included 21st century presidents as well. After all there are bad foreign policy presidents . . . and then there is George W. Bush. The decision alone to go to war in Iraq, an unnecessary and pointless conflict based on dubious intelligence and hyped threats of nuclear, biological attack, would place Bush squarely in the cellar. Yet there is so much more. In making the case for war, Bush ran roughshod over the international system that his own country had helped to form; angered and undermined key allies and cratered the US image in the world. A failure to prioritize post-war planning ensured that a successful military victory against Saddam Hussein turned into a long-term and disastrous occupation that weakened America even further. It's pretty hard to fight a war that literally does not one thing to further US interests and strengthens the enemy you nominally went to war against in the first place (al Qaeda), but Bush accomplished that feat.

Iraq also diverted necessary resources from the war in Afghanistan and the fight against al Qaeda (leading to further escalation and American loss of life after Bush left office). Bush's second term Freedom doctrine to spread democracy around the world failed badly and opened up the US to charges of hypocrisy (it also led in part to a Hamas government taking over in Gaza). And Bush offered little response as North Korea officially became a member of the nuclear club during his presidency. Bush supporters will argue that it's too early to judge the success of his foreign policy performance. Perhaps, but early judgments are in; and they're not good. It's pretty hard to imagine any situation under which that judgment will be reversed.

*This sentence originally referred to LBJ as Kennedy's "predecessor."

**This sentence originally mistook Iran for Iraq. We regret the errors.