Implementation of evidence-based programs and practices is a topic that has received increased attention recently — and rightly so as more laws, grants, and other policies are beginning to be adopted with evidence requirements.

What does it take to implement (i.e., successfully replicate or scale) an evidence-based policy or program? As more organizations have begun to explore the topic, we are beginning to find out.

Thus far, however, a related topic seems to be largely missing from the conversation — politics. Politics is centrally important to implementation for at least two reasons. First, it creates the legal authority, funding, and other capacities that are needed to implement a program effectively. Second, politics does not stop when a law has been enacted. It continues throughout the implementation process.

Evidence-based Implementation

So what do we know about implementation? A good starting point would be any of the following frameworks or activities, all of which are focused on implementation in an evidence-based environment.

These frameworks and activities are already contributing enormously to our understanding of how evidence-based practices are implemented in the real world. Still, one topic seems to have been downplayed in this body of work. What role does politics play in implementation?

There has been some research on the role of politics and evidence in policymaking more broadly. The (perhaps unsurprising) conclusion is that evidence only marginally affects such politics-centric decisions. This conclusion mirrors that of a similar look at the Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative and its efforts to help states become more evidence-focused.

But those conclusions are about politics and policymaking. How do politics and implementation interact?

The Politics of Implementation

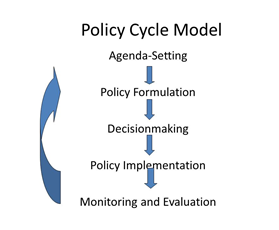

As it turns out, politics and implementation are tightly intertwined. Politics plays a central role in the policymaking process overall — and implementation, as part of that broader process, is no exception. One framework put forward by James Anderson envisions policymaking as a cyclical process that includes agenda setting, policy formulation, decision-making, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, followed by a repeat of these steps as new policies are considered.

Why is this framework important? First, politics shapes the policies that are being implemented. As Patrick McCarthy, president of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, wrote in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, “the road to scale inevitably will run through public systems.” Those systems are shaped by politics.

Second, the implementation process is itself inherently political. The political science literature gives numerous examples:

In short, implementation is not immune to politics, it is driven by it. Politics chooses our elected officials, influences the adoption of evidence-based policies, creates the capacity and infrastructure needed to implement them effectively, and influences the choice of high-ranking appointees who oversee their implementation.

Policies that lack buy-in from those who are tasked with overseeing them will usually be poorly implemented. Even indifference can be fatal, since change always faces an uphill fight when it confronts the status quo.

Evidence Pathways

Given the importance of politics, how does it affect the implementation of evidence-based programs and practices? It appears to do so through at least three different evidence pathways:

All three of these pathways are influenced by politics and public policy. This includes the bottom-up pathway, since such work commonly relies on public funding.

Policy Drivers

So how do politics and public policy influence these evidence pathways? They appear to do so through at least five sets of policy drivers:

Example: Evidence-based School Improvement under ESSA

So how do these policy drivers and evidence pathways work in practice? One example can be found in the current implementation of ESSA, the K-12 education law that replaced No Child Left Behind (NCLB). ESSA includes significant new evidence requirements, which states are currently in the midst of rolling out.

One important focus of the new law is Title I funding for low-performing, low-income schools. These schools have been subjected to all five of the policy drivers at one point or another since the Elementary and Secondary Education Act was first adopted by Congress in 1965, but especially under NCLB and the School Improvement Grant (SIG) program. ESSA is continuing the focus on these schools. They are a central focus of state planning processes, which are currently underway.

These state ESSA plans have been closely tracked by Results for America, whose work so far suggests that there has been substantial variation in their support for evidence. Nevertheless, even a quick review of the plans shows the policy drivers in action. They include relatively low-pressure persuasion-based policy drivers like needs assessments and technical assistance, mid-level incentive-based drivers like grants in aid, and harder authority or coercion-based drivers like accountability frameworks. Local planning efforts will probably also utilize variations of these same policy drivers.

While this process, and all of the policy drivers described earlier, are top-down, the on-the-ground reality is that politics continues to play a dominant role — and it runs both ways. Bottom-up political influence acts as a countervailing force that can (and does) effectively limit the use of the various top-down policy drivers.

These political mechanisms were powerful enough to drive Congress to replace NCLB with ESSA. They played a role in the related Common Core standards efforts. They probably also greatly explain the variation now seen in the state ESSA plans, probably because of varying partisan and ideological leanings among the governors, state legislatures, and other players. These political differences also largely explain state variations in legal authorities, budgets, personnel, and other pre-existing state and local capacities that are needed for implementation.

Conclusion

Implementation of evidence-based programs and practices — at least for public programs involving health, education, and social services — is inherently intertwined with politics.

Implementation involves much more than narrow technical issues like fidelity, capacity building, continuous improvement cycles, and evaluation. While each of these issues is vitally important, they are nevertheless part of, and fundamentally driven by, a much larger public policy cycle that is inherently political.

Politics should be an integral part of any implementation model. A better understanding of the role of politics will be critical to implementing evidence-based policies effectively.

Related